Provider Personas

Putting User Perspectives Front and Center

Background

In the summer of 2016, I joined Denver Health, Colorado’s primary safety-net hospital, as an instructional designer. I was charged with helping inpatient providers efficiently use the hospital’s new electronic health record (EHR) software, known as Epic. Among other things, providers use the EHR to view patient vital signs and lab results, write notes, and place all their orders for medications and procedures.

Denver Health had switched to Epic about five months before I arrived, and as is the case in many hospitals, the transition was rocky. Many providers viewed Epic as a time-wasting burden that interfered with patient care, while some of my colleagues informed me that providers were prima donnas who refused training, ignored communication, and didn’t collaborate well.

purpose

Clearly, there was a disconnect between my team of developers and trainers and the users we were meant to help. I need to bridge that gap, and while I cared about the specific frustrations the providers had with the EHR, I knew I could best help them if I understood them as people. They didn’t feel like training was worth their time, but what was worth it? They didn’t like using the EHR, but what did they like about their jobs? I needed to align my training and communication with their values, and develop solutions that suited their perspectives. Shadowing users to learn their workflows was standard practice on my team, but I decided to do more direct user research and create user personas.

process

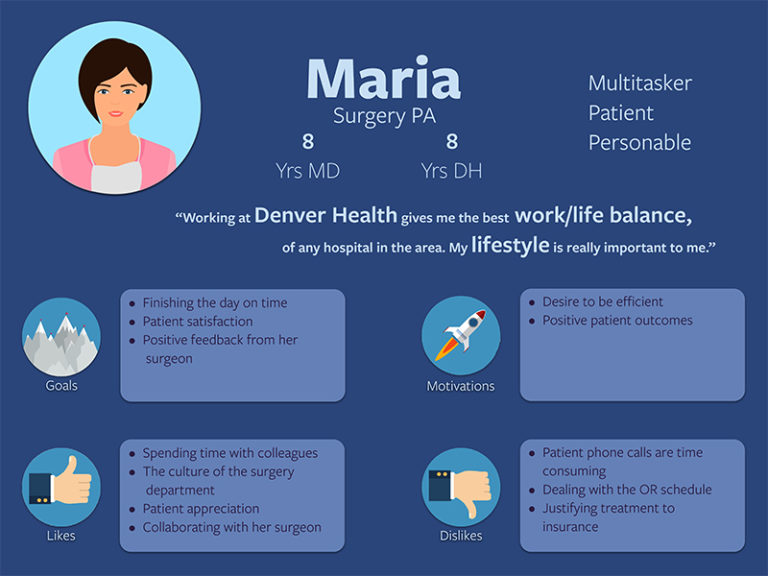

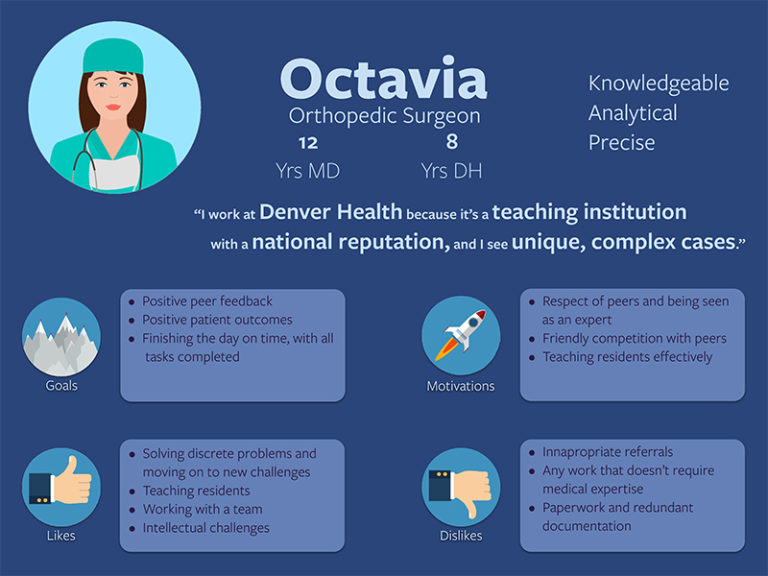

My user group had hundreds of individuals with over a dozen specialties, so to make the task more manageable, I focused on the three largest specialties: internal medicine, pediatrics, and surgery. Within those groups, I would interview nurse practitioners, physician assistants, attending physicians (those who have completed their residencies and are employed by the hospital), and residents, physicians who rotate through different hospitals to complete their training.

I developed an interview script with questions falling into four categories:

- Technology Usage – How does the user feel about digital technology, and how does it fit into her life?

- Learning Style – How does the user best learn new information, and what people/resources does she rely on?

- Epic Experience – How comfortable does the user feel with Epic, and has it been a net positive or negative?

- Work Experience – What does the user actually do, and what motivates her?

I interviewed a few users, keeping the conversations for just fifteen minutes out of respect for their busy schedules. Questions from the work experience category were the most generative, eliciting longer and more emotionally rich responses, and I revised the script to prioritize these. From those initial interviews, I used snowball sampling to find other interview subjects, eventually interviewing twenty providers over the course of four months.

To analyze the interviews, I grouped the providers by specialty, wrote all the responses to each question on separate post-it notes, then grouped similar responses to look for patterns. Periodically, I pulled in coworkers to check whether my logic was making sense. Each specialty took about 5 hours to analyze, and in the end, I produced three personas for each.

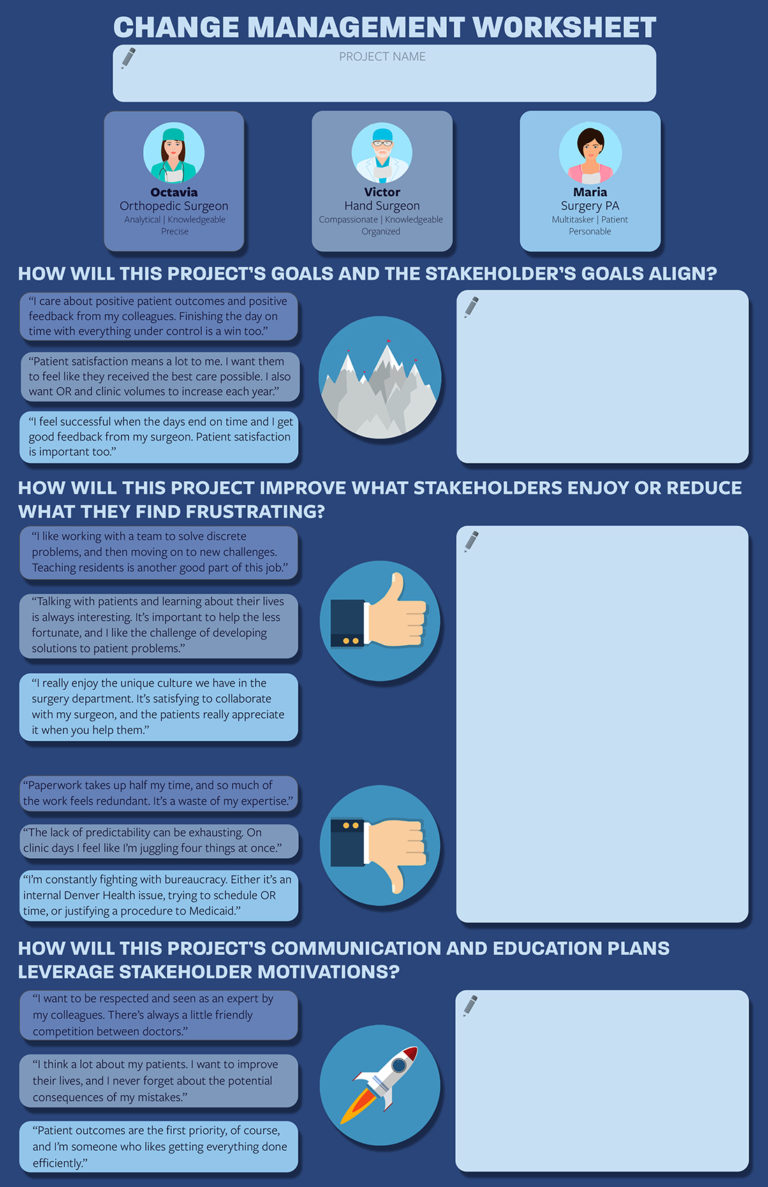

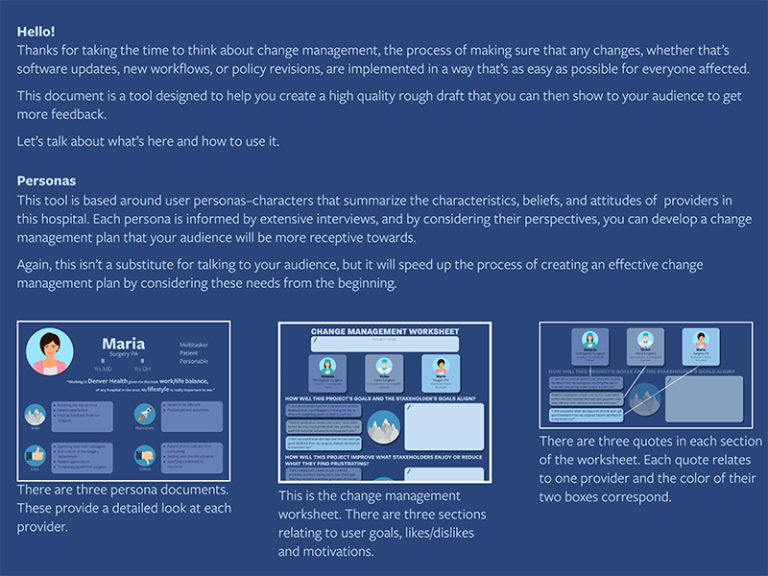

I sought feedback from my supervisor and a project manager to see if other users could benefit from the personas. The project manager suggested that the personas could be useful for change management, and I created a worksheet for this process. This tool was meant to guide someone through a series of questions to ensure that user perspectives would be incorporated at the start of any project. While it wouldn’t substitute for including stakeholders in project planning, it could save time at the earliest stages and serve as a means to develop ideas for user feedback.

Outcome

From the interviews, I gained a deep appreciation for how many of my users saw working in the hospital as not simply a job, but as a calling. While answering a question, one resident teared up as he descried what it meant for him to work with some of the more vulnerable patients at Denver Health. He thanked me for the chance to stop and reflect on the meaning of his work, a rare opportunity in the frantic life of a new doctor. Coming to understand how my users saw their work also helped me see mine in a new light. I felt the reality of Denver Health’s mission, and grateful and humbled to play a small role in that important work.

The personas themselves proved useful for the rest of my time at Denver Health. I referenced them regularly, and the insights I gained from the project particularly informed the work I did developing materials for intern orientation, and for weekly communications. I also presented on the process to Denver Health’s Epic leadership team, and to my fellow instructional designers. My supervisor kept the printed copies of personas posted in her office as references for herself and as examples of how user research could inform training design. In 2018, I gave a presentation on design thinking to 40 instructional designers at the Epic XGM conference, explaining how they could use personas to improve training quality.